Written August, 2021

June 22, 1986

Yokusuka Naval Hospital, Japan

We landed atYokusuka Naval Air Base on Tokyo Bay. The non-ambulatory were loaded onto buses with stretcher racks. Several of us walking wounded marines got on a bus with bench seats and IV cables strung above us to hang our bags of drugs. It looked like evening in Japan. The ride through the local town was interesting, including the locals who gave us hostile looks. I don’t remember what kind of food we got on the 8 hour flight. I know I was really hungry and my bowels were getting freaky. We had been warned that the antibiotics we were given, because of the high doses, would wreak havoc on our digestive system.

From: “When I Die I’m Going to Heaven ‘Cause I’ve Spent My Time In Hell” A Memoir of My Year As an Army Nurse in Vietnam, by Barbara Kautz

“When I tell people today what we used for antibiotics in Vietnam they are dumbfounded by the doses and the drugs of choice. Antibiotic doses were enormous; Chloromycetin had such terrible side effects its use in the US was limited. But in Vietnam we needed to use every possible tool at our disposal. The rich soil of a Vietnamese rice paddy, fertilized by human waste, created a truly frightening bacterial soup in which men on patrol routinely stepped.”

Getting off the bus at the Naval Hospital was kind of exciting. Maybe my first leg of a journey back to the USA?

Wished I could have walked into the hospital, but safety requirements mandated being in a stretcher. There was an urgent need to eat or dash to the toilet, but I had no freedom to go anywhere, nor did I know where anything was. We were taken to the Orthopedic Ward and put into a bed. Eventually, the walking wounded and some marines in wheelchairs were escorted to the mess hall which was huge. It was challenging walking with an IV pole and carrying a food tray through the food line, but the motivation was there. The food was plentiful and delicious. The marines at our table were bitching about how these Navy folks get such great food and we had been fed garbage. A few guys were talking about how lucky we were right now to be out of the bush. Some reported seeing a plane at the air base unloading caskets.

As expected, the talk turned to asking everyone how they were wounded, what kind of “action” they had seen, and how long they had been “In Country”. Thus, establishing status, and determining if you suffered enough to earn respect from your peers. Rank wasn’t just the stripes on your uniform. It was your time In Country and in the bush. There had to be formal and informal ranking so all would know who was beneath them, who they could order around, and disrespect. I was pretty close to being the most “cherry” of everyone and got a little blistered from the conversation. That motivated me to make several trips to the ice cream dispenser.

That evening a Red Cross volunteer came to our bedsides and gave us each a goodie bag of necessities like toothbrush, slippers, shaving gear etc.. She told us that we might be able to call home in the next couple of days. There is a time and date difference between Tokyo and Chicago so it would take some planning to coordinate a call.

I remember that the ward was very noisy from loud talking, screaming from dressing changes, and flashback nightmares. It was a big echo chamber. I crashed hard anyway.

I was awakened later on and had an exam by the night shift. Because I was spiking fevers they determined that I should take additional antibiotics orally. So my IV had to stay in for now. It was difficult to sleep with a cast on one side and an IV on the other.

The next day was a big day. Got to go to the mess hall on my own and wander the halls a little bit. Just had to be back in time for medical rounds. Had a huge breakfast and a real toilet. Still no shower. My guts were behaving unpredictably. Soon enough a Doctor, Nurse and Corpsman appeared at my bedside. I knew I was going to get my first dressing change and had been warned by other marines that it was awful. When they pull away the dressing from the wound it takes scabbed blood, dead skin, and some live skin off with it. The nerve endings are antagonized.

The doctor was very matter of fact and waited while the nurse gently pulled my bandages away from the wound. It was shockingly painful. The warning I had received was not exaggerated. I was stunned, thought it was over. Then the corpsman opened a package and handed the doctor a pair of shiny scissors. The doctor started cutting away at dead skin around the margins of my elbow, “debriding”. It was the worst pain I had ever felt in my life, (or would ever feel again). He was dissecting me without any additional pain medication. I was ready to faint and when he stopped I asked for some water. The doctor nodded to the corpsman who rolled up my pajama leg and stabbed me in the thigh with a syringe.

It felt like what you might imagine a heroin rush to be. I was on a 15 second magic carpet ride until I passed out. I didn’t even get to sip some water. I don’t remember my state when I woke up but I basically continued my routine as a patient in this hospital.

Here I lie,,, in my hospital bed,,,,tell me,,, Sister Morphine,,,, when are you coming round again?

“Sister Morphine”, Rolling Stones

On Sunday morning, June 23rd, I got to make the call home. It was Saturday evening in Chicago. I knew my parents would be home drinking and playing cards with their friends, the Thompsons, which was the Saturday night routine.

The Red Cross volunteer helped me work the phone. She told me that my family had probably gotten a telegram already, notifying them about my injury. My mom answered the phone. She said they were expecting a call because they did receive a telegram that morning. It was quite a shock to them but not a total surprise. I assured her that I was ok and we talked about what happened to me. “We thought you were guarding a bridge”, she said. I told her that was my story so they wouldn’t worry. My dad got on the phone and asked if if they were going to send me home. At that point I had no idea. Anyway, it was good to get that off my mind. We all agreed that it was good that I was out of harm’s way even though there was some damage done. I probably cried sometime during the process, but I guess that was ok considering the circumstances.

My parents received this telegram a few days after the call. I’m guessing that the marine corps clerk who composed the telegram was stoned or hung over or both. There were errors on wound information, my current location and the spelling of my father’s name. Or, to be fair, maybe he was overwhelmed with his work and in a hurry.

Over the next few days I got to speak to an MD a couple of times about my situation.

The main issue was that I had a bad infection and they couldn’t proceed with the skin grafting until that was resolved. I finally got brave enough to ask if I was going home. They said they could not tell yet. But if they got everything under control and I had a good skin graft, I could potentially return to Vietnam because I still had about 9 or so months left on my 13 month tour of duty. That was very depressing. So what do I do? Hope that the infection rages on and proceeds to a bone infection? Some of the marines in our walking wounded group suggested that I secretly pretend to take my oral antibiotics but spit them out after the nurse leaves. I couldn’t see myself doing that. I wanted to get rid of the infection, fevers, dressing changes, get my IV out and move on to the next step. One of the marines who suggested this, had been shot in the left hand. It was fairly common for men in Vietnam who had been in the bush too long, to stick their left hand out from their covered position during a firefight. Hoping to catch a bullet in the hand and get sent back to the “world”. The guy denied that when the other marines challenged him on it.

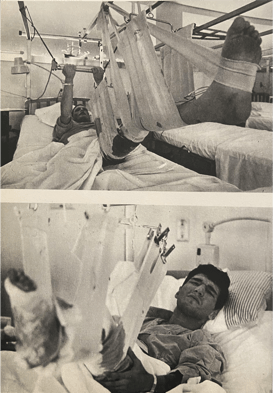

I was getting bored watching TV in the “Day Room”. “Bonanza”, a popular western TV series, was the only TV show that was entertaining. The dialog was in Japanese and it was very funny to hear these big tough cowboys speaking to each other in a strange dialect. Out of boredom, I began to roam the halls. There was an Orthopedic Ward, (where my bed was), a Neurosurgical Ward, and a Burn Ward adjacent to it. All the wards were massive with two long rows of beds along the two longest walls. There were nurses and corpsmen hustling from one wounded marine to the next. Outside the Neurosurgical Ward there were marines sitting in wheelchairs in the hallway. These poor souls had brain injuries often with missing parts of their skulls. These marines would never have a normal life. It was horrifying to see the damage done. I don’t care about this war. There is no threat to our country. I don’t want to go back.

I got up the nerve to walk the whole length of my ward to see if there were any familiar faces/names. Maybe I could find the guys that were lined up with me when we “assaulted” the tree line. Maybe someone would know what happened to Johnny.

I could read the identification board at the foot of the bed. The marine’s name, unit number, and date of injury were on the the clipboard. There were a lot of marines in bed in leg traction who were able and eager to talk to someone, anyone.

There were amputees, some with 2 limbs lost as well as some head trauma. There were quite a few delirious or agitated men who were begging for help, or screaming about their misfortune. There were dressing changes going on. It was too much to handle, so I made my outings brief.

Eew!, that smell, infected and dying flesh.

I had my second dressing change a few days after the first. I got pain meds a couple hours beforehand. It wasn’t as brutal as the first, just removal of bandages and kind of a light scrub of the area. Very painful, but nothing like the weaponized debridement of a few days ago. The doctor said that there was not much improvement and they would try to decide my future needs at the next dressing change.

I was hoping to get my seabag delivered to me at the hospital. I had my camera and some good pictures and my letters from home. No-one could tell me if I would receive it at this hospital. Really wanted to have some walkin’ around clothes.

My immediate hope at this point was to get my IV out so I could take a modified shower, (with a plastic bag wrapped around my cast). The sponge baths, assisted by the lower ranking male corpsmen, were incomplete and getting old. My highest hope was to have the MD decide that I need to go home for ongoing care. And no, I didn’t spit out my antibiotics or dip my elbow into the toilet. I was hearing that bone infections are really damaging and can cause total body sepsis. (The body responds to a severe infection by attacking the organs and other tissue).

It was probably the 28th of June when I had my last dressing change here. The doctor said that I had a very stubborn infection and my care would last too long to stay here in Yokosuka. They were going to send me stateside for care. Probably to Great Lakes Naval Hospital, about 50 miles north of where I lived. I got excited and asked the doctor if I was going to be discharged. He looked a bit irritated, didn’t know, probably tired of being asked that question.

I’m going back to the “World”. Hurry up, book my flight.

I probably flew out June 30th. My records show I arrived at Great Lakes on July 1st.

We stopped in Anchorage Alaska for refueling, and St. Louis to drop off some of the wounded who lived in that area.

The flight was awful. Happily, I got my IV taken out because the flight was too crowded

due to the huge casualty count. The walking wounded were put in the front of the plane in seats with metal frames and netting for seats and backs. The rest of the plane was set up like it was on my inbound flight. There was an open space in front of us, like a lobby, where the nurses gathered supplies, prepared medications, cleaned instruments, and maybe sat down for a few minutes. There was one stretcher bound patient in this area, right in front of us, mounted on a gurney of some sort. He had severe burns all over his body from a white phosphorous munition. White phosphorous, (WP), grenades were used to suck the oxygen out of tunnels. WP was also fired by artillery or dropped from planes. This was probably a friendly fire incident. WP burns to the bone like napalm. This poor marine was going home to die with his family present. Even though he was mostly covered with a sheet, the nurses had to uncover him to tend to his needs. I have never seen anything so horrible. He was often screaming in agony and we would beg the nurses to give him more morphine, for his sake, and for our sanity too. (Shamefully, these types of patients were called “crispy critters” after a popular cereal of the time). We all wished that he would die soon so his family would not have to see him like this. As we would wish for ourselves.

The nurses and corpsmen taking care of this poor man were so hard working and patient with him. They could occasionally get him to talk about where he lived and his family. He did not want his parents and siblings to see him in this condition. “Please let me die”.

It was very uncomfortable and difficult to sleep during this 12 hour flight to Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage. The plane was bumping and banging through the air causing everyone to howl in pain. It was a big relief to get off the plane and stagger into the base cafeteria. It was summer twilight, very late at night, and the fresh air was a tonic. We still had another 6-8 hour flight before we would get to our final destination.

After a quick stop in St Louis, we finally arrived at Glenview Naval Air Station in the northwest suburbs of Chicago and got on a bus to Great Lakes Naval Hospital

We all had so much respect for and trust in the nurses and corpsmen at Yokosuka Naval Hospital . They were amazing.

Memories of Navy Nursing: The Vietnam Era Compiled by RADM Maryanne Gallagher Ibach, USNR

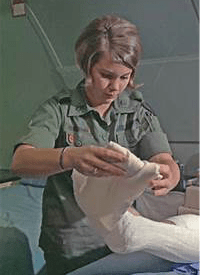

I was a “novice” nurse when sent to US Naval Hospital,Yokosuka, Japan in April 1968. Our patients, mostly Marines and Navy hospital corpsmen, were “fresh from the field.” They’d been triaged and initially treated, but were generally a day from the horror. When I think of those two years in Japan, I remember all those young men… – thousands of them – rows and rows in perfectly lined-up beds on open wards – serious, sad, scared…desperate…eyes – some to recover and return to “Nam”, more evac’d to the States, once stabilized – many never to recover – the open wounds that defy description – how could they survive those wounds?

I remember… – the 19 year old triple amputee who planned to be a sculptor – before the war – before he lost both arms and a leg

I remember… – the smell of pseudomonas

I remember… – the pain of dressing changes

I remember… – the cries in the night

I remember… – their nightmares…their memories…memories they often couldn’t describe – only their tears told

During those 2 years I learned the senselessness of war and understood the loss of innocence of all who were there – who listened, who cared.

(Mariann Stratton, NH Yokosuka, April 1968-70, Director, Navy Nurse Corps, 1991-Present)

7-1-68 Great Lakes Naval Hospital, North Chicago

We got some waves and horn honks from people on the bus ride to Great Lakes Hospital. It was so good to be close to home. Couldn’t wait to find out the visitor policy, and make some phone calls. I had no idea how long I would be spending here. Just patch me up and discharge me is all I ask.

Don’t remember much about getting admitted to the hospital. Same as before, long rows of beds in the Orthopedic Ward. Same old crowd lying in bed or siting in the TV watching area. I’m still in pajamas and slippers, maybe a robe, but free of the IV pole.

I got to make a call to my parents. They said that they would come and visit the next evening after my dad got off work. After relinquishing the phone and waiting a few hours I got to call my girlfriend, Mary Ellen. (All of these calls were “collect”, meaning the recipient had to pay all charges, which were quite high.) We were both excited to be able to see each other. She had already arranged to ride up with my parents.

That evening I got a shower with a plastic bag wrapped around my cast. It was wonderful except for the corpsman standing by a few of us to make sure we didn’t do anything stupid. Then I got my cast removed, a deep scrub of the wound, dressing change, and new cast. 1*

The next night I had five visitors. My mom, dad, sister Cathy, 10, brother Pat, 15, and Mary Ellen. We all sat out in the lobby and had a good time. Some of the walking wounded stopped by to chat, curious why I was so popular.

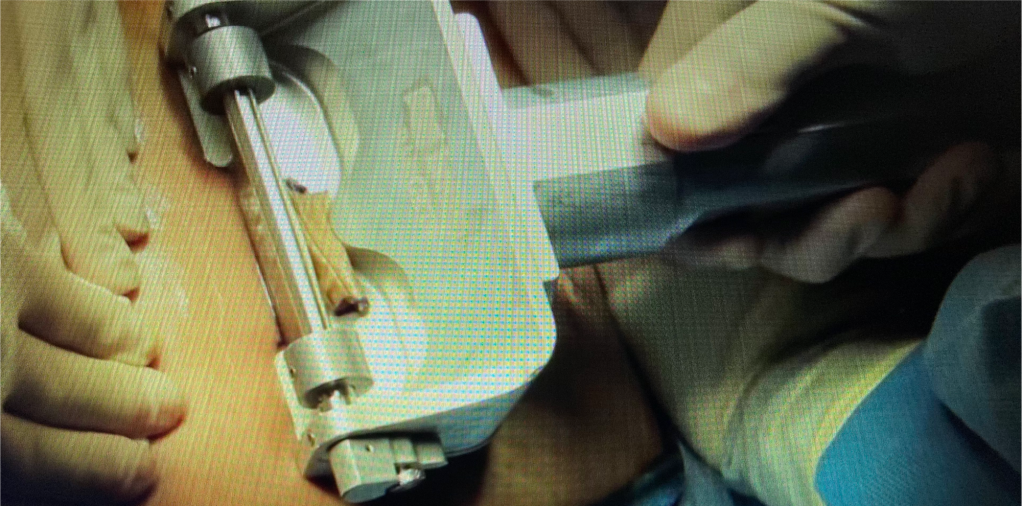

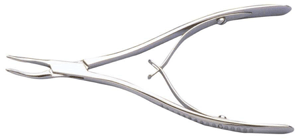

On July 9th, I had my skin graft done. A special tool called a dermatome slices off a portion of skin, usually from the opposite side thigh, if that area is available.

I was taken to the OR, put under anesthesia, cast removed, and wound scrubbed. Skin was taken from my left thigh. The skin was put into a tool to puncture holes in it, turning it to a mesh type of material. The grafted skin was then sown into my wound and packed with a moist dressing. A dressing was also put on my left thigh donor site.

When I returned to my bed, I was a bit more disabled than when I went into the OR. Stinging soreness of the left thigh, IV in left hand, and soreness in my right elbow from the stitches. They also had mobilized my right elbow joint somewhat, i.e., moved it into flexion and extension to prevent joint adhesions. I got a new cast. It was great. Better fit. Better smell. The next few days and nights were a little rough but the pain meds helped. I was on crutches for a few days to protect the donor site from trauma.

My parents visited frequently that week, which was nice, mostly because they brought my girlfriend along. Later on the family visits were reduced because of the 2 hour commute. Mary Ellen came up to visit occasionally, borrowing my parents car. My mother was unhappy that she didn’t fill up the gas tank or reimburse them. That put a damper on our visits for sure.

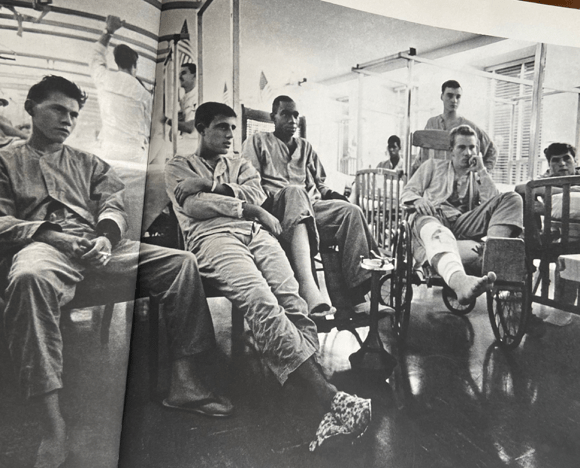

Little by little I explored our Orthopedic Ward. Most everyone had at least one major bone fracture. Many others also had amputations, burns, or facial injuries. Many were in traction and maybe one fourth were “walking wounded”, with arm, rib, or skull injuries. The walking wounded might be on crutches or in a wheelchair, but mobile.

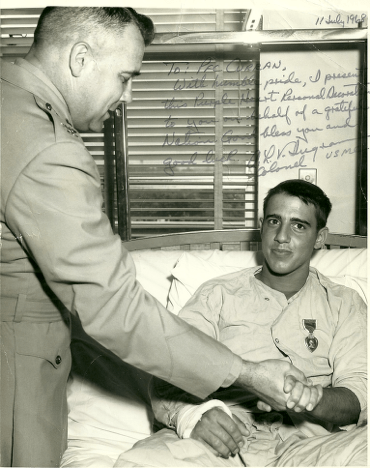

On July 11th, while I was still 18, I received a Purple Heart Medal from a high ranking officer who came to the hospital to hand out this award to eligible marines.

To qualify for a purple heart you have to be injured as a result of combat or hostile enemy activity. You didn’t have to shed blood to get a purple heart. If the armored personnel carrier that you are riding on rolls over a mine and you get blown through the air, crash into a tree breaking multiple bones, and shattering your eardrums, you are eligible. This happened to my neighborhood friend, Jim Shupryt. You don’t even have to be wounded by the enemy. You can be severely burned by an accidental drop of a white phosphorous bomb on your position by US aircraft, like the poor marine who was on our flight to Japan.

I started Physical Therapy in late July. I was wrapped in a split cast which could be removed for exercise. My arm was really stiff from being in one position for so long.

Bending and straightening of my elbow was only a total of 40 degrees out of a normal 140 degrees. Forearm rotation, (palm up, palm down) was also limited. Apparently someone wanted to “nibble” dead bone off my elbow, (see above). I had been using my hand as best I could and I hadn’t felt weak until the cast came off. I was a bit alarmed at the stiffness of my elbow and weakness of my whole arm. The “Physical Therapist” was a Corpsman with special training. He would gently do range of motion on my arm, trying to increase range. I eventually graduated to using some small weights. The graft was healed enough to receive hydrotherapy. I put my arm in a small, warm/hot whirlpool bath and tried to get more straightening of my elbow. That was very helpful.

It was determined sometime later in July that I was fit enough to be useful as a helper in the ward. I was one of very few who could stand at attention at the foot of the bed as the Physicians/Officers came into the ward to do rounds. Patients had to sit or stand at attention until the doctor saw them, unless of course they were too mangled to sit up straight in their beds. This was to continue our Marine Corps tradition of reverence for rank and authority.

I resented having to do that and I resented having to be a helper. I enlisted to kill communists, not be a hospital attendant. But ultimately, I was grateful for my assignment. It reminded me every day that I was the luckiest marine, (out of over 1200), in this hospital.

My job was runner, message taker, well-being checker, TV tech, urinal transporter/emptier, and anything else that could be done with 2 legs and one hand.

I delivered TVs to the bedside according to schedule. Then responded when my name was yelled in the ward. “PFC Curran, assist with tv… “. Change channel, adjust volume, set rabbit ears antenna to get reception. Then come back as scheduled and bring the tv to somebody else. If somebody fell asleep while they had a tv, I was told to yank it and give it to the next marine on the list. Some of the jarheads didn’t notice, and some complained to me, but there was really very little worth watching. It was just a way to confirm that you were back in the USA.

There were more serious ways to provide help. The more severely wounded guys had other needs. Scratch an itch, untangle bedding, adjust the pillow, or help with the telephone.

There were a few of us lightly damaged marines who performed these duties on some kind of rotation. Sometimes it was difficult because of the frequent contact with badly injured marines. Often they wanted to talk for long periods. I was too immature to give them what they needed, so I would keep moving, on to the next customer. It was tough to see a girlfriend or mother come to visit an amputee for the first time. All the ambulatory marines would leave the area to allow for some privacy, freedom to cry out loud.

Some marines wanted me to help them smoke in bed, which was forbidden. They would get pissed at me for denying them that favor. They solicited me to steal pain pills for them. Sorry, no can do. Another “off the books” request was from post operative patients who wanted me to fill their pee cup. The nurse would come by with a catheter and say, “ if you don’t fill that cup, this is going up”. I was begged many times to go to the bathroom and fill the cup with my own urine. Sometimes, cash was offered. I was tempted at times to do it, because I knew I would beg for the same favor if I was in their position.

All this “running” kept me from going crazy with boredom. I spent too much time thinking about my part in the war while I wasn’t busy. What was my contribution? I was grateful that I didn’t cause anyone to get killed or wounded. But the thought of Johnny, possibly dying, trying to help me, weighed heavy. I wondered if I would ever know. I wasn’t troubled by “Survivor’s Guilt”, and felt a little guilty about that. Was I hiding/suppressing my feelings? I wondered if I would ever get my belongings that were left in the bush, especially the letter with the address of Johnny’s girlfriend.

Overall, I don’t feel that I did any good for the “cause” in Vietnam, whatever that was. But I knew I would never be the same person that I used to be. Even so, I vowed to go back home someday and resume my life exactly how I left it.

The only other activities of my day were examinations during medical rounds, and a dressing change every few days. The dressing changes continued to be difficult, but now I knew that I had it easy. There were only a few square inches of skin graft to pick and probe on me. Others had multiple dressing sites. The screaming in the wards every day told the story.

On my “breaks” from helping in the ward I would roam the hospital just to get away from the misery. The hospital was packed, way over capacity, with over 1200 marines and a

few paratroopers. The ambient noise level was maddening. Sometimes I would sit in the lobby or outside on some benches. Naval officers, including hard corps nurses, and

other military lifers would pass me and order me back to my ward because I wasn’t “dressed” properly. Ok, get me some clothes.

One day I happened upon the chapel and decided to hang out in there. It was good to have silence and a place to get away from the sights and smells. But it didn’t do anything for me spiritually. That part of my being seemed to be fading. The chaplain frequently made the rounds of the wards, and a Catholic priest came and held Mass on Sundays. I didn’t really want to get involved with either of them. Having close contact with a priest brought up some weird memories of my days as an altar boy. 2*

In August, I started asking for a weekend pass to go home. The answer was no for the first few requests, and that really pissed me off. I didn’t care that they had good reasons. I just wanted to go home. By the middle of August I had been in three different hospitals for eight weeks. I needed to get out and breathe the air, drink some beer, kiss my girlfriend, sleep in a quiet peaceful room, wear clothes, and shoes. I decided to not ask anymore. Maybe that’s the secret for having your dreams come true.

At the end of August, 1968, the Democratic Convention was being held in downtown Chicago and there was trouble from day one. Ten thousand war protestors flooded the city. Mayor Daley mobilized the entire police department. Thousands of National Guard troops were brought in. The protestors consisted of hippies, college students, young people not interested in being drafted, clergy, press, and every other conceivable category of citizen.

The police and National Guard tried to clear Grant Park and the front of the Conrad Hilton hotel where the delegates were staying. The protestors fought back.

They were maced, billy clubbed, kicked and had their heads slammed against the paddy wagons that carried them to jail.

These confrontations went on for several days. One day during the convention battles, hospital authorities came to the ward and told us that NBC News wanted to come to the hospital and take photos of wounded marines. They wanted to do this to show what the fighting in the streets was all about.

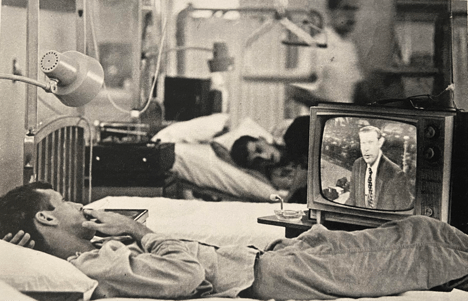

Most marines on the ward agreed to be photographed, including myself. We had been watching the battles on TV every night and were reminded of how crazy our country had

become. The convention delegates were mostly old white men, well marinated in alcohol and tobacco smoke. Many of them thought we should fight on in Vietnam despite the opinion of a majority of Americans.

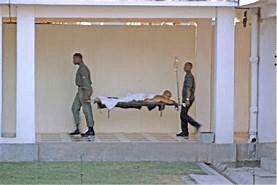

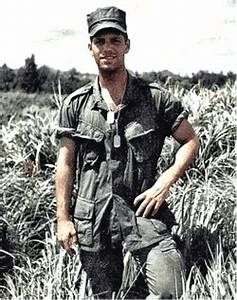

He was an ex-marine combat photographer during WWII and the Korean War. He was also a good writer. He showed up that evening after our dinner. The hospital photos, (other than my purple heart presentation), and the one delegate photo above, were taken by him.

This is what he wrote on the page next to the picture above:

“The hospitalized veterans from Vietnam, those bandaged men already ambulatory, or in wheelchairs—-not the newly arrived of course, with wounds still draining and legs and arms suspended in traction slings……watched the convention and anti-war demonstrations without comment. No rancor…no recriminations…no second-guessing combat strategy…no contempt for hippies, no matter how unshorn; hatred for flag burners…no judgement on policy-makers, a world so remote from their own as to be nearer fiction; like the western (tv show) being watched by that grunt down the ward. Then there were the blind, broken, burned, who saw nothing.”

*3

The visit by Duncan was perceived by some of us as a hopeful sign that maybe these photos would move some people to change their view of the war. Naive?, probably.

It was hard to know what to think about the war. I was immature and lacking knowledge about Vietnamese history and the true threat of communism. My opinions would sway back and forth depending on how the last discussion went.

That week my medical situation started to change for the better. I got a good report at dressing change. Graft infection was reduced, the fractures were somewhat stable and healing properly. I was offered a weekend pass! Actually a four day leave, probably because it was Labor Day weekend. I think I headed home on Thursday the 29th. Us lucky marines were sent downstairs to a little storage area to get uniforms. It felt great to get some clothes and shoes on. Some of us walked to the commuter train station near the hospital. We headed for downtown Chicago where I would transfer to a train to the south side. One of the guys with us was John Pollock. We graduated the same year from high school. He was an acquaintance, not a friend. He had a shrapnel wound to one of his knees, bad enough to take him out of the game. He talked like a badass but was a bit foppish. He often came and hung out in the lobby when Mary Ellen was visiting. He was the third wheel. I had noticed him around the ward, limping around with his cane with a painful kind of walk. Occasionally, I saw him outside the ward, when he thought he was alone, with a pretty normal walking pattern. A scam in the making.

We rode the train downtown, excited abut our homecoming. We had no thoughts about what we might encounter related to the war protests, but all hell broke loose when we pulled into one of the downtown stations. When the doors opened a mass of young people came charging into the cars as if they were running for their lives.

Some of them looked beaten and disheveled. Pollock got up from his seat and raised his cane over his head shouting some derogatory terms to the “hippies”. I had to get up and pull him back to his seat. He seemed relieved. The new riders told us that the police were chasing them. They looked genuinely afraid. It was awkward for a while but we got off the train shortly after, to transfer. The potential for conflict was over.

I can’t remember the details of arriving home, (something that should create a strong memory). I was really glad to see my brother and sister in our home setting. I spent time at home and with Mary Ellen and some friends.

One thing that stuck with me was that our family went out to dinner with some local aunts and cousins. My mom insisted that I wear my uniform. I made it clear that I did not want to. But, it was all about her, to show me off like a trophy.

Numerous people at the restaurant came up to me and said kind words, and asked personal questions. They could see I was in a cast and put two and two together and decided it was ok to probe. Well-meaning, but I didn’t want to talk to strangers. Without thinking, I ordered a steak and when the waitress placed it in front of me she said, “do you want me to cut your meat honey”. Well, no thanks. Maybe my mother or girlfriend can help me with that. If I was back in the mess hall I would have picked up the steak and eaten it with my left hand. But here I am, away from the zoo, in a nice restaurant. Someone sent a round of drinks to our table. That helped.

During the Vietnam War, as in other wars, families with members serving in the war effort were given small flags with a star on it, to honor the service of the family member(s). We had two “star flags” on our front door. My brother Mike was on an Air Force base in Thailand where air strikes were launched on Vietnam. I suppose the star flags would incentivize the families to allow their sons to be “blinded, burned, and broken”. Republicans, and many Democrats, often recited the common sayings of blind patriots: “Better Dead Than Red”, “America, Love it or Leave It”, and “Bomb Hanoi”.

So having a star flag posted at your house was some form of what?…I do not know.

“Take the star out of the window, and let my conscience take a rest”

“Take the Star Out of the Window”, John Prine

All in all it was really great to be home for a few days. The down side was having to go back and live in the hospital for who knows how long. I was watching the days and weeks glide by, wondering how long I had to stay on the disabled list before it was too late for me to go back to Vietnam. Or, even back to duty in the states. So far, I had only put in 9 months of my 2 year enlistment. Healing and getting back tonormal was the top priority for me, but created big risks for my future. I didn’t know how to stop worrying and live in the moment.

I had some friends left on the south side who weren’t away in the military or college. A few of the guys drove me back to the hospital. The way they drove was terrifying. They drove exactly like I used to. Not being in a car on the expressway for a while had left me unprepared for the speed and recklessness. I was relieved to get out of the car at the hospital and get back into my safe place.

I had one more weekend pass before my next procedure. Going home was a little easier, without the convention chaos and the crazy friends. My Uncle Andy and Aunt Barb were visiting from Cleveland. Got to hang out by the pool at their hotel.

The Navy Corpsmen continued to earn my respect and admiration. There were all kinds of horribly wounded men in the PT gym. Amputees, brain trauma, fractures, burns, all packed into a small area. Everyone cheered the other marines on in their struggle to get better. Some of the guys made no progress. The Corpsmen moved from one patient to the next for a few minutes at a time.

Eventually, I could go to the PT department, fill the whirlpool, work my arm in the water, and do most of my other exercises on my own.

My healing was going well except that I needed another procedure. A protrusion of dead bone at the pointy end of my elbow had broken through the skin graft. I ended up with a procedure called a sequestrectomy. Under anesthesia, they took a big tool like a wire cutter and snapped off the dead piece.

They took another small slice of skin from the same place on my left thigh. Full cast, (not split), no showers or weekend passes for a while. I bounced back from that pretty quickly and continued my rehab.

October rolled around and I was anxious to hear my fate. I was categorized with “6 months limited duty” without a specific assignment. Recruiters were working the hospital ward. They approached the marines who were going on light duty. These stiff necked, hard ass lifers were offering us to “up” our enlistments to 4 years in exchange for “choice” assignments, such as “Sea Duty”. That involved being “hall monitor”, security guard, referee, and jailer aboard ships at sea to keep wayward sailors in line. Another option was to go overseas on Embassy Duty. All American embassies are guarded by US Marines. All I could say was “no thank you, sir!”

Around this time I was checking out the chalkboard “schedule of procedures” out of curiosity. I saw the name Charles Lofrano, a high school friend of mine from an adjacent neighborhood. He was in surgery that day. I went hunting and found his bed on the other side of the ward. I hadn’t noticed that he was there. While there, I ran into Cary, a friend of his from training who was also from Chicago. Cary hadn’t seen “Chuck” yet but saw his name on the board too. We decided to be his welcoming committee when he returned from the recovery room. Lofrano was a really good friend in school. We took most of our classes together. I didn’t know that he had joined the Marines. He was happy to see us when he woke from his anesthesia. He was in the 27th Marine Regiment also, fighting in the same area where I was wounded. He had a really bad arm wound with damaged nerves and paralysis of his wrist and hand. His life would be changed forever.

From that day on Cary, Chuck and I hung out together. Along with a few other walking wounded we became somewhat of a nuisance for Navy Staff. I had been anxious for

some relief from the dull, institutional, robotic routine. It was time to bust out, like we had as seniors in high school.

We held a wheelchair race in the hallway for the somewhat able bodied patients.

Chuck Lofrano tells the story in his book, “In Spite of it All”.

“We were becoming infamous in our ward …….,,,we organized a sit-down strike in front of Captain Wallace’s office to protest the suspension of our phone privileges. Earlier that week we had staged wheelchair races down the main hallway of our floor. It was quite an event…,,,,. We probably would have gotten away with it except for the long, ugly, dark rubber skid marks on the navy’s immaculately scrubbed floor. The punishment for our “Wheelchair 500 Race” was to have no phone rights for two weeks. After a two day sit-in, a thorough scrubbing of the floor and a promise never to repeat the event, we were reprieved.”

Our group shared stories of our experiences. We had many things in common, but the one problem that was universal was constant ringing of the ears, (tinnitus). Some of the guys had asked their doctor about it and were told that it would go away. So, I guess we let it slide.

Lofrano and I had a lot in common. He went to USMC Boot Camp three months after me, was wounded in the area of Vietnam where I was wounded, three months after me. He was treated at Yokusuka Hospital and then Great Lakes. He also went to the University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus after his discharge, as did I. He left Great Lakes before me to go to another hospital for multiple surgeries to try to repair the nerves in his arm. When he left he was optimistic about his recovery and return of his hand function. The guys in our group could all see that his hand was dead and that there was no bringing it back to life. We kept those thoughts to ourselves. Lofrano and I lost track of each other at some point. I discovered his book a few years ago. It was disappointing to me that he was so angry and bitter after 40 years. He died of multiple heart problems in 2011.

“For a heart stained in anger,, grows weak and grows bitter

You’ll become your own prisoner,, as you watch yourself sit there,

wrapped up in a trap,

of your very own chain of sorrow”

“Bruised Orange”, John Prine

I have read quite a few books about the war, maybe 20. All written by combat veterans. They were written 30, 40, 50 years after the fact. As far as I know, none of these authors were seriously physically damaged by the war. Many had some degree of PTSD. Not one of them thought the war was legitimate, moral, sensible, logical or winnable. In fact, they called it unnecessary, insane, criminal, immoral.

The book by my friend Chuck Lofrano was the exception. Written in 2011, Lofrano’s book sounded like a manifesto from Fox News. He used terms like “cowards” for draft resisters and war protestors, “arrogant self righteous elites” for University professors who talked about America’s many flaws, and “America haters” for those who criticized the war or the government.

I have noticed over the years that men who were severely damaged by the war have a hard time saying that the war was foolish, wrong. Doing that means that their life was destroyed by mistakes made by the US government with the support of a majority of Americans. Therefore, there was no good purpose for their sacrifice. I can understand that survival mechanism.

There was another guy in our walking wounded group who was pretty badly damaged. His foot was mangled and he needed a brace to walk. Something that would affect him forever. And, he was getting a dishonorable discharge for shooting himself in the foot in the middle of a firefight. He denied it, with a wink. We didn’t hold it against him. He seemed to have ADHD, maybe mild Asperger’s. Not that a diagnosis like that was required to want to shoot yourself in the foot to get out of the bush.

My recovery was going well. In October I got orders to go to Camp Pendleton on ”Limited Duty”. I was really disappointed, crushed actually. I was foolish to think I would get discharged. I got a leave of absence and ordered to report to Camp Pendleton on November 14, 1968. I would have a full year left to serve in this big green machine. Light duty until April 1969. I didn’t know how I would handle it. But, there it is, don’t mean nothin’.

I left Great Lakes after nearly 4 months of hospitalization at 3 hospitals. I had not seen repeated, bloody carnage during my short time in Vietnam. But, while in the various hospitals I saw the damage and suffering that lingered long after the wound was experienced. I witnessed the sorrow, frustration, pain, and loss of hope that the seriously wounded marines, and their families, suffered every day. There is no end to the pain when someone is so badly damaged. I left Great Lakes feeling extremely lucky to be relatively unaffected by my Vietnam experience. I also felt sorry for myself because I had to finish my enlistment.

“The Dogs of War don’t negotiate

The Dogs of war won’t capitulate

They will take, and you will give

And you must die, so that they may live”

Pink Floyd, “Dogs of War”

Footnotes

*1

*2

Father John Hennessy was one of the priests who performed Sunday Masses at our church. I “served” at his Masses when I was in eight grade. He would get the two of us altar boys in the preparation area and talk weird. Then he would pinch our upper shoulder muscle until we dropped to our knees in pain. All the while he had this creepy, scary laugh. Every kid I knew had been physically abused by adults to some degree or other when they were growing up. So, I just thought this priest had his own cruel way of hurting children. It never occurred to me that there was a sexual component. Later as an adult I realized that he was probably grooming us for some type of sexual encounter. I don’t remember if I ever told my parents. Nothing ever came of it.

“Lying with his eyes while his hands are busy working overtime” “Happiness is a Warm Gun” The Beatles White Album

3*

I never found out what happened to the photos and mostly forgot about them. There was no way to know where they landed. Then, I ran into one of my friends from Great Lakes Hospital, Danny Mallman. He was another lucky marine with a million dollar wound. We passed on the sidewalk on the North Side of Chicago in the late 70s. He told me that the pictures were in Duncan’s book, “War Without Heroes”. I spent many years searching for this book and eventually gave up. The Dewey Decimal System wasn’t working for me. I did find a copy of the book in the late 80’s, (Barbara Gilbert), but the photos weren’t in it. When I started writing about my Marine Corps experience, I did more research on Duncan. I found his book about the 1968 Democratic Convention, “Self Portrait: USA”. I contacted an Amazon vendor who had it for sale. He verified that the book had photos of marines in the hospital. Bingo! Amazon did the rest.

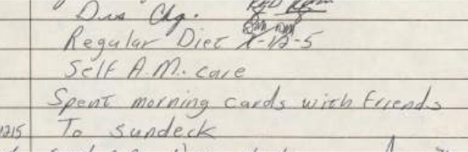

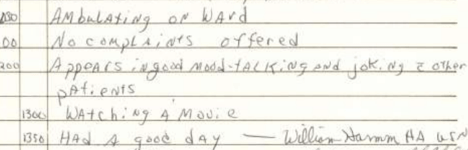

Days at Great Lakes through the eyes of nursing staff