Written June, 2020

It was around mid May of 1968. My assignment to B Company, 1st Battalion, of the 27th Marine Regiment landed me in a tent camp at the Danang Combat Base. This was home for the regiment, (about 3000 marines). Combat missions were launched from here and this was our “basecamp” when returning from the “bush”. There was heavy combat all across Vietnam since early May when the enemy launched another large offensive. Marines were being kept out in the field for longer periods of time and casualties were very high. The 27th Regiment, parts of which were now rotated to the rear for a short rest, had been under continuous sniping, ambushes, night attacks and full scale firefights. Hatred and defiance of officers and sergeants was out in the open. The regular grunts felt that the “lifers” were risking the lives of everyone with their aggressive combat tactics. New officers made foolish, deadly mistakes. And there were no obvious beneficial results from the incessant combat. The only results, aside from widespread destruction, were dead and maimed civilians and troops from both sides.

When I showed up I was assigned to a tent with some empty cots in my platoon area.

I picked a moldy, filthy cot where some sullen, angry marines were hanging out. They looked terrible. Emaciated, sores on their legs, awful looking feet and emotionally vacant. I got the usual hazing that was required by marine corps tradition. After all, to them, I was an FNG. (“Don’t make friends with a dead man”.)

There was one bunker for every two tents, reflecting the frequent mortar and rocket attacks in the previous months.

The chatter in the platoon area was that RFK was going to be President and maybe

President Johnson would call a cease fire in the meantime. That sounded good but maybe a little overly optimistic.

Most of the troops seemed to support RFK except the lifers and the southern boys. The lifers didn’t believe in ending the war because war is what lifers dream about. The southern boys didn’t care for RFK’s goal of achieving racial justice.

Racial tension on this base was high, higher than in Phu Bai. Apparently there had been some large scale racial fights on the base with some gunfire and serious injuries.

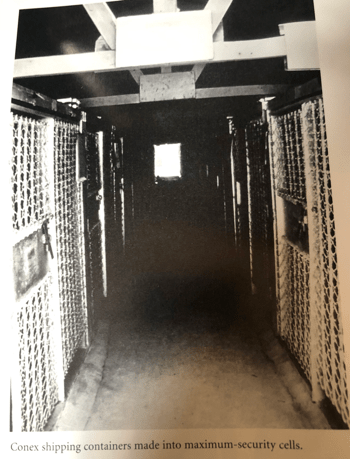

The experienced grunts were despondent and terrified of going back to combat. Some were working on various schemes of self injury or sickness. The brass were on high alert for slackers. If you were caught sickening or injuring yourself you weren’t referred to a psychologist. You would face court martial and time in the brig, (military jail). There were many prisoners in the notorious, overcrowded Marine Brig at Danang and the Army Jail at Long Binh.

With all that said, I could only concentrate on my next meal, the next time I could

go to sleep, and where I might be tomorrow. This would be my “home” for the remainder of my 13 month tour of duty.

Things started to happen fast. I was told to get my gear together for guard duty at a bridge for two nights. The next morning me and another new guy got on an open air truck with other marines and headed out from our area. When we got away from the basecamp we were told to turn outward with rifle barrels on the rail to be prepared for any attack that may come. We stopped at a bridge over a large river. The bridge was a link between the farmland and the city of Danang. It was also used by the VC to infiltrate the city and set up commando squads, make attacks, and get supplies for their fellow soldiers. There was undesirable activity happening in both directions of the bridge. It was the responsibility of the 27th Marine Regiment to maintain possession and security of the bridge.

When we arrived at our end of the bridge, (Bravo Company’s turf), we saw our heavily armed defensive bunkers on both sides of the road. There were marines posted down at river level also. Bunkers for sleeping were set back from the bridge. The word was that the city of Danang would be attacked again, and this bridge needed to be held. Our group was there to guard the land around the bridge.

Our mission was to patrol and search for any people with bad intent. We walked through farm land around a series of villages. There were 8 or 10 of us. It was 100 degrees. Fortunately, we were advised ahead of time not to wear our flak jackets.

We had to confront random farmers and other civilians and check their belongings and see their IDs. Our squad leader was very intense and efficient with this. The locals seemed to know the drill and could say “me no VC” in English. I personally did not search anyone. I was just on watch for trouble, hopefully in the shade.

It could have been a nice walk in the rice paddies and shady groves, but the harassment that we were dishing out was not pleasant. The recent and ongoing offensives by the enemy resulted in little trust of any of the local population.

We could hear firefights and explosions off in the distance for most of the day but nothing disturbed our patrol.

The farmers went about their business in the midst of the war as if it was normal. They looked worn out and numb.

When we returned for the day, a crew from the nearest mess hall came out on a truck and delivered a hot dinner. I was homesick for my duties in the mess hall.

Some marines at the bridge had slept during the day and were now on duty for the night, manning guard posts at various parts of the bridge complex. This bridge was a critical choke point for access to Danang so there were probably 20 or 30 marines on bridge duty on each end. Some of them were Military Police, skilled at search and interrogation. There were also South Vietnamese soldiers on the bridge for interpretation and security support. Sometimes at night the bad guys tried to cross the river in small boats.

There was a lot of chatter in the sleeping bunker. I was hearing things that were disturbing. There were descriptions of abuse and the killing of innocent civilians. Villages that were considered friendly to the enemy could be torched. Rape was apparently a common occurrence also. Those who reported these crimes were often disregarded by senior officers and risked retaliation by fellow troops.

My 2nd day of patrol was with a different group of marines. We were working the other side of the river which was more forested. We took long breaks. Our squad leader was being merciful because of the heat. Or he was lacking enthusiasm, or both. I heard more marines talk of the desire to get sick or injured to avoid further combat. They said that we were getting our asses kicked in our area of operation. My earlier enthusiasm for this adventure was nearly evaporated.

Our group got on a truck on the 2nd morning and headed back to our basecamp.

So far, I had made it through 4 outings in the bush without firing a shot or seeing any enemy troops. Every trip to the bush was mostly with a totally different group of marines. I never knew their names for more than a day. Most of them had nicknames anyway. When somebody died, their nickname would often go to an FNG.

Back at camp I was told that I missed mail call and was directed to go to the mail shack.

What a great surprise to get a packet of letters and a box. I was excited because a previous letter had informed me that a package of goodies was coming, but I figured it was lost or stolen.

I sat down somewhere private near the mail shack and opened a letter from home. There was the usual news about stuff going on in Chicago. More importantly, I was informed that George was in Khe Sanh. This was a hilltop base close to the southern border of North Vietnam. It had been in the news consistently as a besieged base at risk of being overrun. There were 5000 American marines there that were surrounded by about 20,000 North Vietnamese soldiers. There was continuous bombardment of Khe Sanh by enemy artillery.

George was part of a mortar team defending the base. I felt bad that he might be suffering and in grave danger.

Nevertheless, I decided to open my package since I was somewhat out of sight. There was a box of Salerno Butter Cookies and several boxes of Junior Mints. (yes, I heard about George’s predicament and stopped to have some junior mints.)

I didn’t have any friends to share them with at this time and was aware that theft of personal belongings in the hooches was common. I decided to eat the whole bundle right then and there. The boxes of junior mints were crushed and the contents had melted many times over. It was a squashed cow pie of delicious candy. I scraped every molecule out of every box with my teeth and fingernails. Then I ate all the butter cookies. It was wonderful. I did not feel the least bit guilty about not sharing. I had no connection or loyalty to anyone at this point.

The next day was a round of orientation to learn the chain of command of B Company and my platoon as well as signing off on my will and completing details of my life insurance policy.

Maybe that night or the next, there was a small USO (United Service Org) show scheduled in our area of the base. I tagged along with some of the neighborhood marines. It wasn’t like the big Christmas shows with Bob Hope and some sexy stars like Ann Margaret or Raquel Welch. It had a Vietnamese band playing American rock loudly and badly, then some sexy American dancers in scanty outfits.

For the moment it was a good distraction. After it was over, everyone was acutely homesick and wondered why we were being tortured like this. It only made things worse.

On the way out of the crowded show area, I ran into a friend from boot camp, also from Chicago.

He suggested we go get our 2 beer allotment at a nearby cruddy little beer tent.

We had a pretty decent time and he invited me over to his tent to hang out.

When we got in there I was ready to turn around and go back to my own tent. This dwelling was nearly totally covered in sandbags and was very dark inside. It was full of angry looking black marines. There were Black Panther and Malcolm X posters on the walls. They looked at me like I was dinner. My friend, Araujo, was Puerto Rican so he was accepted by the inhabitants. He lived in a far corner of the tent. He told me if he had to choose, he would rather be black than white. I had heard of these places. This was a “Black Shack”, no whites allowed. They were smoking dope and I could hear them talking about how they would get weapons when they got home, start the revolution, and “kill whitey”. A stream of black marines were coming in and out and getting the gospel about our racist country and this racist war from some of the apparent leaders. I didn’t stay long. It was awkward. I was very afraid.

I made it back to my area and before I hit the sack I decided to write to my parents and tell them that I was safe on a big base. Even though I knew we were going to the bush soon I told them that my job for a while was to be guarding the bridge. That way they wouldn’t worry too much. I didn’t know at the time that there was a fierce battle at the bridge a month or two earlier and there were a lot of marine casualties.

In the morning our platoon had the usual line up outside our tents for roll call. Let’s see if anybody ran away last night. Our platoon sergeant told us that our regiment was going to continue to be heavily involved in the defense of the City of Danang during this major offensive by the enemy. We would be heading out to the bush soon to continue participation in Operation “Allen Brook”, so keep your rifle clean and get your gear packed and ready to go. We will be out for a long time.

One of the experienced marines, a muscular black man, started grumbling and walking away from formation before we were dismissed. The platoon sergeant called him out and said he needed to stay with the platoon and get with the program. He called him “brother”. The black marine said “don’t call me brother, ain’t no white man my brother”, and walked back to his tent. That was the first time that I saw open defiance and disrespect go unpunished. Things seemed to be unraveling. I did hear and experience, that in the bush, racial tension was not so bad because every marine had to rely on every other marine.

I got called out after roll call and given my promotion to Private First Class, (PFC).

Wow, they finally caught up to me. I think it came with a $20 per month raise. I was sent to the supply warehouse to get a fatigue shirt with one stripe on it. There is a whole chapter to write about supply sergeants who act like they are giving you their own property. It was required to express gratitude for getting one lousy item of your uniform. There were abundant stories of them selling cases of beer and soda etc., that was intended for the troops.

The rest of the day was spent collecting and packing gear for the long outing that was ahead.

I was packing my toothbrush and realized I hadn’t brushed for a while. My teeth were feeling nasty and sore on one side. My hygiene was suffering and it was going to get worse in the field. The basecamp had toilets, (barrels for crap and some smelly urinal type things). Showers were in an outdoor screened area and there were specific times that you could use them. Grunts returning from the bush had priority. Water stations and sinks for washing were few and far between. Lines were long for everything. Drinking water was foul unless you got your hands on some Kool Aid packages that were often gone before you could get any in the mess hall. (Brushing and rinsing with Kool Aid water might be an incentive to brush). Being an FNG, I hadn’t figured out how to work the whole system yet. Maybe I would get better oriented when I returned from this operation.

In the days that I was at basecamp I saw the big picture of the manpower that was in place. I had been to the supply warehouse, mess hall, mail tent, show stage, beer tent, headquarters office (to sign my promotion papers), and had seen all the support vehicles driving around with starched officers and their drivers. Somewhere on the Danang Base there was some kind of shopping mall where you could buy reel to reel tape recorders and upscale cameras and almost anything from America. The fact was, that about 15-20% of all marines were sent out to the bush for combat and the rest were support troops. Seemed out of balance, but I certainly would accept a job in an office being a manservant for one of the officers. The guys in the rear had bunk beds with mattresses and bedding. *2

The marines in my tent suddenly started treating me like I was one of their team. They filled me in on important issues about being in sync with the platoon and B Company.

Watch for booby traps and old fighting holes that had covered with grass that you might fall into. One marine talked about the extensive tunnels where we were going. He told me it was dangerous to be a tunnel rat but maybe safer to be in a tunnel than exposed to the heat. The truth was that you were as likely to be a casualty of nature as by combat. Lack of deep sleep, leeches, rats in the fighting holes, heat stroke, trench foot, (from having wet feet for too long), dysentery from the water, dehydration from excessive heat and shortages of water resupply, malaria from the ever present mosquitoes. We had received inoculations for diseases like plague and typhus. Time for rest and recuperation had been reduced making fatigue a constant which led to poor judgement.

On another cheerful note, there was a high incidence of death or maiming among the FNGs due to lack of experience and subsequent mistakes. Getting blown away before they had a chance to really suffer, before they even got a nickname.

This shop talk was intermixed with bold talk of what they would eat when they got home and all the horny/manly/studly things that they would do to their women or all women. There were a lot of shallow dreams floating in the air, as opposed to my sophisticated dreams of wet kisses and Junior Mints.

Also, many bragged about how we were going to “Get Some”, meaning, killing the enemy. There were a lot of feelings of revenge for lost friends. They hated the enemy because they wouldn’t come out into the open and fight. They would watch us from concealment. Watch us until the heat got us, or a sniper, maybe a booby trap. Then they would fire on us when we were totally exhausted or distracted and then hit the road before we could organize a counterattack.

“Dear John” letters were a common thing for troops in Vietnam. Lovers back home had trouble waiting during the 13 months of absence of their partner. Many troops were shattered by this whether it was a wife or a girlfriend. Suicide by heroism was somewhat frequent according to the “word”.

B Company was scheduled to go to what was called Go Noi Island, to replace another company which was being relieved for rest. Go Noi Island was more of a delta surrounded on three sides by rivers and about 15 miles south of Danang. The enemy had launched attacks from there during the Tet Offensive in January and was reorganized again to try to take Danang. The local population was considered very friendly and supportive to the NVA and Viet Cong. Fighting had been constant and vicious for the whole month of May.

“Casualties on both sides had been heavy. For the entire operation through the end of May, the Marines reported to have killed over 600 of the enemy. They themselves sustained since the beginning of the operation 138 killed, 686 wounded including 576 serious enough to be evacuated, and another 283 non-battle casualties that had to be evacuated. The number of heat induced “non-battle casualties” had soared towards the end because of the extreme high temperatures averaging 110 degrees and the physical exertion expended in the firefights. In many engagements, the number of heat casualties equaled or exceeded the number of Marines killed and wounded.” *3

At the same time, RFK had won the Nebraska and Indiana Democratic primaries.

Hopes were high among the troops even though the convention was not until the end of August. Unrealistic hope is better than no hope.

At the end of May, B Company, 1st Battalion was ordered out to the Goi Noi Island area as planned. We knew we were facing dreadful circumstances, but me and the other “cherries” didn’t have much experience to grasp what was coming. The night before we were to leave was revealing. Someone brought a case of warm beer to the hootch and we all partook. Some marines from the platoon area brought in another marine who was despondent and looking for help. He had a “premonition” that he was going to die on this “Op”. He was offering $100 for someone to break his hand so he wouldn’t be able to go. He was begging and pleading, close to tears. Apparently he had already been wounded once and was very fragile. His buddies said that they didn’t want him out in the bush with them because he was a liability. I am embarrassed to say that after no one came forward I stepped up to take him up on his offer. I was under the influence and felt sorry for him. Mostly, I wanted to get some cred from my team. (the $100 sounded good too—almost a month’s pay). I don’t remember if someone provided a brick or a hammer. He put his hand on a table and told me to do some damage. Fortunately, that little voice kicked in and told me that this was wrong and crazy and I would go to the brig as well as regret it for the rest of my life. I stepped away to the booing and jeering of the marines that were present. Time for me to grow up.

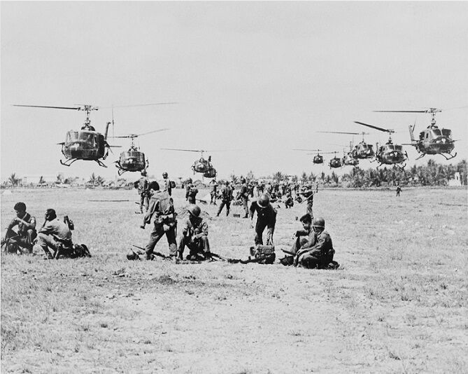

B Company, about 100 plus marines, assembled at the LZ the next morning for our insertion into the Goi Noi Island area.

Coming in from the air you could get a peek of the land which was deformed with bomb craters, partially burned out villages and shredded forests. This area had been bombed for several years.

We were inserted by the Hueys without incident and immediately started a sweep of a large area, following a map pattern with pre-designated potential hot spots.

I could tell this was going to be serious by the amount of ammo we were carrying.

I started out with a can of machine gun ammo and a few LAAWs in addition to my personal rifle ammunition. When we stopped for a break we had a briefing by a platoon sergeant about the current situation. This area was heavily layered with fortified bunkers, tunnels, booby traps and hundreds of enemy troops who were also able to hide in the protective bunkers that local villagers had built for their own protection. That meant that distinguishing friend from foe was even more difficult. However, we were still obligated to protect non combatants from injuries even if it meant hesitating for a moment to think about opening fire on someone. A civilian may be running because they are afraid, but not necessarily because they are helping the enemy. (a civilian running away on the approach of American troops was often taken as permission to shoot). I was a little relieved that there seemed to be some level of sanity in these instructions. There had been a lot of press coverage about American troops crossing the line and indiscriminately killing civilians and the pressure was on to follow the rules of war. “Fire control” was a priority for our own safety as well as the civilians. Be practical. Don’t turn them against us any more than they already are.

The long “hump” started on a route connecting a series of villages, “villes”. It was totally draining. Walk, stop, walk, hear gunfire in the distance and hustle to a firefight which was over before we got there. The company was spread out over a wide area so it took a lot of coordination. Officers were on the radio checking in and consulting with platoon leaders. Where the hell are we going? Nowhere. Just walking around like bait.

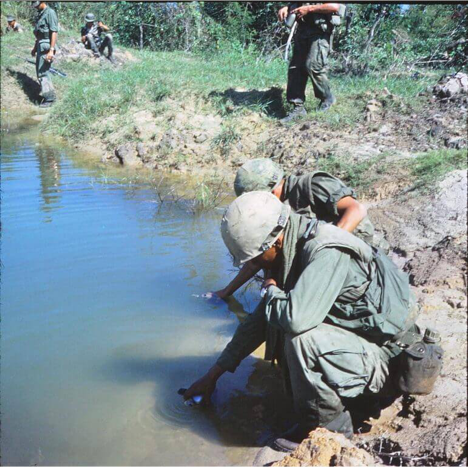

We were all ordered to fill up on water at every opportunity. Many casualties were due to heat stroke which could be fatal. It was at or over 100 degrees. We were told that a lot of those suffering heat stroke were “shitbirds” who were too lazy to carry enough water and suffered the consequences. At each water stop, squad and platoon leaders checked our gear to see that all of our canteens were full.

Still, some marines wasted their water by pouring it on their heads or even throwing some away to avoid carrying it.

It was quiet in the villes. We knew that if the farmers weren’t out working the fields, they must be hiding in their bunkers because VC and NVA were in town. Or maybe it was too damn hot. In the afternoon, marines started to get sick because of the heat. There was a sergeant who was older, maybe 40. They called him gramps or geezer behind his back. There was talk of him not making it through the day. It turned out to be true. He eventually went down from the heat and needed a corpsman. The poor guy had to go out on a medevac chopper which was coming in to pick up a couple of casualties from snipers and booby traps. We did the best we could to find some shade while we waited for all this to be done. This seemed to be a game only for young boys. Most of the troops had just graduated from, or dropped out of high school. But we weren’t doing very well either.

We stopped a lot for breaks and to interrogate the random civilians that were out. There were scouts/interpreters with us from the South Vietnamese Army, (ARVN). They tended to be aggressive and threatening to the locals.

We went through our water quickly. I tried to ration the few packets of Kool Aid that I had.

At first the walking was done very cautiously. Measure each step and carefully look at the ground to make sure that where you put your foot down is safe. Eventually, you just stagger along, not caring.

All I noticed other than exhaustion, was that my teeth were getting more sore and my jaw was swollen. It was clear to me that something was really wrong inside my mouth.

Finally we stopped at our “home” for the night. Everyone started digging in. Aside from our fighting holes, we had to dig straddle trenches for pooping. Of course the FNGs had this assignment. We weren’t allowed to use one of the several fighting holes that were already in existence from past visits by marines. Enemy mortar crews definitely had these coordinates dialed in from previous encounters.

But first, clean your rifle.

During this long day I got a lot of advice and instructions on everything. Hand signals, knowing whether shells flying above us were incoming or outgoing, how to use smoke grenades so we wouldn’t get fired on by jets or helicopter gunners, all the jargon that was used for things I didn’t know about anyway, how to treat a limb amputation to prevent someone from bleeding out. So much to remember. To make a mistake and cost someone (or myself) an injury or their life was terrifying. I was also told that eventually I may have to pick up the radio and assist the platoon leader in contacting headquarters for an air strike, artillery, or medevac choppers. I knew how to change the channel on a TV but that was about it. So leave me out of the radio operator scene.

A lot of marines were talking, while “digging in”, about how many days they had left in country. Every marine had a “short timer” calendar or stick. Some of the guys were so short, they were ready to be taken out of the bush so they didn’t get killed too close to the end of their tour. I was in no position to bother with that kind of accounting. So we ate our nasty food and set up for a long night. Once again, 3 marines in a fighting hole, one awake and watching, one sitting up and ready to fight, and one asleep. We agreed to not sleep on watch and to poke the guy who was asleep if it wasn’t his turn. I’m not sure I trusted their word on that. At least we had an LP (listening post) in front of us and I wasn’t in it.

Sleep doesn’t come easy in a dirt hole with 2 other filthy men. It feels like you are in a smelly closet filled with mosquitoes and all other forms of strange flying and crawling insects. I knew mosquitoes from Chicago, but these were ferocious. When they got near your ears they sounded like bumble bees. If you soaked yourself in repellent, you would be sickened by the toxic smell for hours. Worst of all were the rats. This was my first close encounter with rats. I saw a few here and there in Phu Bai. I don’t think I had ever even seen a mouse back home.

I was asleep and felt a disturbance on my legs and bolted awake. I thought the guy next to me was tapping me awake. He said no, just rats passing through. Ok, now I’m not going to sleep at all. It was a quiet night except that an LP crew got spooked and sent up illumination flares a couple of times in the middle of the night and we all had to be up with wide eyes watching. But there was nothing to see.

In the morning I had to report to the LZ for unloading supplies. While waiting for the Chinook to come in, some random marine wanted to know if I got the word on Colonel Henderson, our regimental commander. No I did not. He was a target for fragging. Long story short, he supposedly lost a company of marines in the Korean war and was trying to rebuild his reputation by tossing us in to the fire. Our regiment had taken high casualties and not been given enough R&R. There was a pool of money to kill him, shoot down his helicopter if he makes a flyover assessment of our area. Big prize money. He wanted me to buy into this lottery. After my encounter with “Break my hand Bob”, I was in no mood for any other schemes. So many hustlers, so many liars, so many blind patriots. That was the Marine Corps. Never was sure if this story was true or a scam to get money from FNGs. That’s what made it so crazy.

After resupply and breakfast, Company B headed up into the hills and into the jungle.

When we split up into platoon and squad I was assigned to another marine to learn more about how to be at the rear of a patrol. It was a dangerous position. Often the point, (front), of a patrol was fired on first. But it was safer for the enemy to pick off a few people at the rear of a column and run away. But at least I wouldn’t get everyone lost, which might happen if I was on point. Just keep up with the marines you see in front of you but keep watching your 360.

It was another day like the one before. Hump all day and at night sleep sporadically in a dirt hole.

The morning was exciting. There was an attack on the company perimeter on the back side of our circle of defense. Naval gunfire was called and one of the shells came in short and hit the top of a very tall tree behind us. There was an awful noise and we were showered with leaves and branches and pieces of hot metal. Fortunately it was only one round that fell short and it was over. The enemy attack seemed to be stopped by the big guns and we went about our business of gearing up for another daylong sweep of the area.

We made a pretty simple stream crossing that day on our journey. We got to make it into a bath break which was very soothing.

It was my first contact with leeches which are in most of the streams in Vietnam. They attach to you and suck your blood. They have to be burned off with a cigarette or have a big squirt of jungle juice, (insect repellent), poured on them. Even though we were given Lucky Strike cigarettes for free, (another advertising experiment by American corporations), I did not smoke. A fellow marine took care of the leech for me by burning the leech off of my arm. Very creepy.

In splashing around in the stream, I think I swallowed a small amount of the nasty stream water which almost made me puke. Later that day my face started to swell more and my teeth were hurting more. I could taste the pus in my mouth. I was clearly deteriorating and decided to request to go back to Danang to see a dentist. While we were on this daylong hump I asked a couple of guys how to proceed. They suggested I talk to the squad leader first. In the meantime we continued slogging through the area.

The front column of our platoon ran into a small group of VC in the jungle and we were ordered to go “online” and move forward toward the enemy while firing our weapons.

It was over quickly. They ran off, or disappeared into tunnels. There were one or two minor wounds and the company set up a perimeter to wait for the medevac chopper.

Seemed like a good time to ask my squad leader about my mouth infection. He pointed me to the platoon sergeant who was with the group waiting at the LZ for the medevac.

Suddenly, my problem didn’t seem so serious. I was pumped with adrenaline and didn’t feel as much pain as before, but was still pretty swollen. Every marine at the LZ looked like they should be in a hospital or on R&R.

I spoke to the platoon sergeant about my teeth and jaw and difficulty eating. He basically called me a slacker and told me to get back to my squad. Humiliated, I made my way back to our squad and tried to suck up my troubles.

Towards the end of the day we needed to refill all canteens for the evening and overnight. Several of us were sent into a nearby village to fill canteens from their well. When we were filling up, several of the male villagers gathered and just stared at us. Two of them were unusually tall. The leader of our group told a few of us to face toward them with rifles ready, (unlocked and loaded). He said that the tall men were probably Chinese soldiers. (There were thousands of Chinese soldiers in Vietnam as trainers and advisers.)

The rest of our crew hurriedly filled the canteens and we rushed out of the village on high alert.

After another day of suffering in the heat we stopped at our location for the night and had to dig in again. I couldn’t get any solid food into my mouth because it hurt too much to open wide or try to chew. My face was swollen all the way up to my left eye. I had a hard time sleeping.

In the morning when my squad leader saw me, he took me to the platoon sergeant. The sergeant was shocked and told me I would go out on the first medevac chopper of the day if the lieutenant approved it.

So we saddled up for another day in the bush. I really tried not to hope for us to need a medevac chopper. But I could tell I had a fever and I didn’t want to collapse in the

middle of all this. It seemed like we were just wandering aimlessly with no purpose, again. “Charlie” knew the neighborhood and we were just bumbling through, looking for trouble.

Inevitably, we had some contact from the enemy and our company suffered a couple of minor casualties and heat stroke.

My squad leader sent me to the medevac LZ to get taken back to Danang. I had orders from the Lieutenant, (platoon commander) to be taken to Danang to see the dentist. I had 48 hours to get it taken care of and return.

Three or four of us got onboard and we were lifted off. The wounded marines looked like they weren’t damaged for life. Anything to get the hell out of this shit storm. Some of us couldn’t help but smile.

I’m pretty sure this was my first ride to the dentist in a helicopter. I had no idea what was going to happen but for the moment I was safe.

References:

*1 https://www.thehistoryreader.com/military-history/long-binh-jail/

*2 In April 1969, 30 members of a combat infantry unit aired their grievances publicly. Writing to President Richard M. Nixon, they argued that “basically there are two different wars here in Vietnam. While we are out in the field living like animals, putting our lives on the line twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, the guy in the rear’s biggest problem is that he can receive only one television station. There is no comparison between the two….The man in the rear doesn’t know what it is like to burn a leech off his body with a cigarette; to go unbathed for months at a time…or to wake up to the sound of incoming mortar rounds and the cry of your buddy screaming, ‘Medic!’”

*3 Portion of History of Operation Allen Brook from http://www.5thmarinedivision.com/operation-allen-brook.html by historians of the 5th marine division:

Glossary

Basecamp The place where you live, on a Base, when you are not out in the field on a combat mission

Bird Helicopter

Blown Away killed or wounded and taken off the battlefield

Boot, cherry a marine who is new in country and doesn’t know shit about anything he is considered dangerous to the old timers because they make stupid mistakes, can’t keep up and get people killed

bush out in the field away from the rear bases

Broken Arrow This term is used when there are radio transmissions requesting artillery, air support, or naval gunfire when your position is overrun by the enemy. It means specifically: we are requesting that you direct your fire onto our positions

C Rations Canned food that has already been cooked

Charlie, short for Victor Charlie — Viet Cong or just any Vietnamese that is considered suspicious

chuck--white man

CH-46 or Chinook—-large double rotor helicopter which was used for insertion and extraction of troops, resupply and medevacs

Corpsman what a “medic” is called in the Marine Corps

Danger Close when your own supporting fire, like mortars or artillery, may land very near because the enemy is in your midst

“dee dee” Get the hell out of here/there quickly (adapted from Vietnamese)

dog tags a necklace worn with 2 metal id tags showing name, rank and serial number one gets pulled off the necklace if you are killed and one stays on you

don’t mean nothin’ it’s all hopeless like saying, “whatever”

Flak Jacket body armor

FNG Fucking new guy (see ‘cherry’ above)

Fragging Trying to commit murder by throwing a fragmentation grenade in to an officer’s or sergeant’s living quarters or fighting hole. A way to get revenge for mistakes, harassment or excessive enthusiasm for combat

Free fire zone Anyone that looks healthy is a target – the area is full of enemy troops and supportive civilians who are considered combatants

Friendly fire when troops are fired upon by nearby troops, artillery, or air strikes due to confusion

get some go out and find and kill the enemy

grunt a marine who is walking in the bush, ready for combat, carrying his gear, weapons and ammunition

Huey Bell UH 1 helicopter; used for troop transport, fire support and scouting

hump walking and carrying your gear, weapons, and ammunition out in the field away from a combat base. The average load was about 70 pounds.

In country — in Vietnam– one is always asked, “how long have you been in country” and that establishes your status

KIA–killed in action (also, “wasted”)

Lifer—– someone who is career military. Often a derogatory term meaning that the lifer put career, military rules and decorum above the welfare of the troops

LZ helicopter landing zone

LP Listening Post A fighting hole placed forward of the night perimeter to monitor enemy movement and prevent surprise attacks. Often assigned to “cherries”. It was dangerous because you were sacrificial bait to absorb the enemy’s first strike.

medevac— medical evacuation usually by helicopter

MIA Missing in action

NCO Non Commissioned Officer a corporal or sergeant who can lead various groups of marines. They are not commissioned officers, but designated leaders.

NVA--soldier or soldiers in the North Vietnamese Army–NVA troops have official uniforms; Charlie has some rudimentary uniforms but usually blends in with the civilian population

overrun— When the enemy has infiltrated or crossed your perimeter in force

the world — back home in the USA– “ I’m going back to the world in 43 days”

salt tabs–– salt, (NACL) as a pill you sweat so much the salt leaches out your body and you could suffer intestinal problems, cognitive impairment, and muscular difficulties

splib–black man

“there it is” no matter how ridiculous, it’s true; I told you so; the marine corps does what it does and Charlie does what he does

WIA wounded in action

A portion of this glossary is derived from the excellent book, “Matterhorn”, by Karl Marlantes. Marlantes was a highly decorated Marine Corps combat veteran in Vietnam.

His book is considered one of the best of the Vietnam novels.