Written August, 2019

In the Belly of the Beast

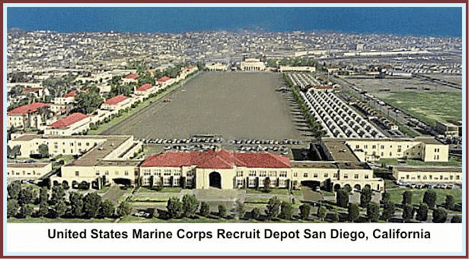

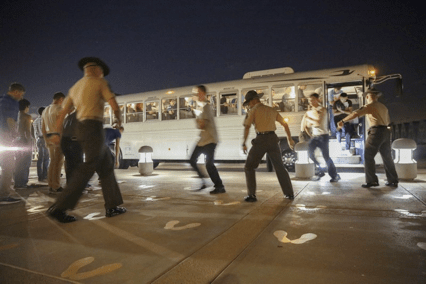

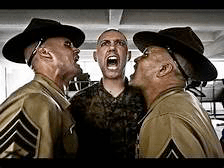

During the short ride on the bus from the airport, the group of recruits from Chicago and a group from Texas had already sounded off as to who were the toughest bad asses in the Corps. This kind of big talk was about to end. Getting off the bus at MCRD was a shock. There was a group of drill sergeants who immediately began screaming at us and calling us maggots and every other possible demeaning term.

“Get in line!” (We will quickly learn that there is always a line to stand in.) First there is a quick and rough shaving of heads. Next, stripped of all clothing and personal items which were boxed up and mailed back to our homes. Then, distribution of uniforms and boots. Within a very short time there was no remaining evidence of our civilian identity. They could do anything they wanted with us and they did. No one was watching.

We stood for hours in the middle of that first night, in silence, on a winding staircase in an old building. Then they let us sleep in our bunks for an hour or so. At daybreak 3 raging lunatic drill instructors screamed us out of our bunks.

Boot camp/basic training is where you are indoctrinated in to the traditions, rules and behaviors of the Marine Corps. And, you get broken down to a physically fit machine that follows orders without hesitation. This is accomplished through verbal and physical abuse, extreme exercise, and food and sleep deprivation. You are not an individual but part of a team of marines. And guess what, it works.

Each day starts with a loud awakening to get dressed and get out on the “road”,

(the walkway in front of your metal quonset hut). Time to run!

It was very clear on the first day which recruits were going to have a tough time. When they were exhausted, they would fall to the ground. Unacceptable.

Resistors and complainers were sent to the “motivation platoon” where they moved rock piles back and forth all day. They came back in a week like obedient puppies. Overweight recruits were sent to the “fat farm” where they exercised all day with little food.

They came back in 2 weeks looking totally fit.

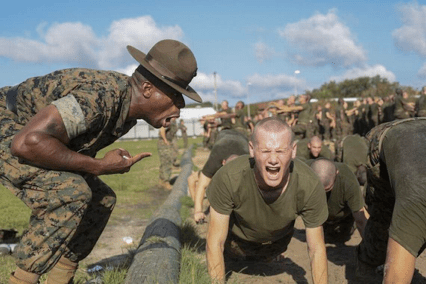

In addition to running there were all the other usual exercises. They loved push ups and jumping jacks until you dropped. If the drill instructor wasn’t satisfied with our performance we were ordered to get in high push up position on our knuckles.

In the first week, our platoon was in the middle of doing endless jumping jacks. George and I observed a recruit with his eyes closed, ready to drop, praying out loud. We looked at each other and laughed. It was all we could do to keep from crying.

Many recruits spoke openly of desertion, jumping the fence and heading home.

However, it was clear that this place was locked up tighter than a prison. The punishment for trying to escape would be worse than the current situation.

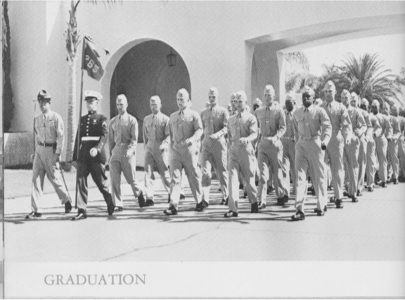

Drill,,, marching,,,, unity of movement. The Drill Instructor was tasked with getting us to march in an orderly and cohesive manner to turn our platoon into a single moving machine.

We did drill work every day for 10 weeks until the footsteps of 76 men sounded like one very big person walking. We marched (or ran) everywhere that we went.

Every recruit got singled out for some form of punishment–including holding your foot locker full of your gear while standing at attention, or being in high plank on your knuckles on the concrete. For some strange reason, I had not yet been busted for anything.

We were in week 2 of our training, and one day 2 drill instructors pulled me aside and asked if I knew Frank Curran. “No sir!”

One of them asked me if I knew that he was the Mayor of San Diego. “No Sir!”

“That’s great” he said, and punched me solidly in the solar plexus knocking me to my hands and knees fighting for air. “That’s for all your fuck ups that we ignored.”

The only thing that kept me going was having George as my bunkmate and being able to look at each other during the day and even smile and laugh once in a while. At night we would talk and quietly giggle at all the weird people and the crazy things we were doing everyday. We were relieved that we came into this situation in good physical condition.

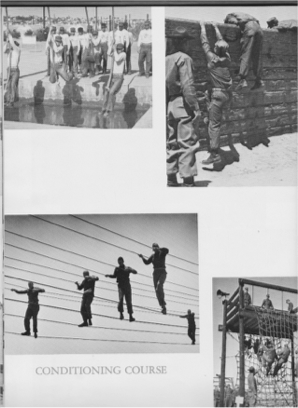

Gradually we had more and more military type training in addition to our normal physical training and classroom work.

Fortunately, we were all emaciated, making everyone lighter to carry.

Things got more frightening as time went on.

We had to learn the “dead man float” in case we had to abandon a sinking ship or landing craft. George struggled with natural buoyancy and had difficulty staying afloat. He had a hard time with this and felt he was drowning. He observed the instructors laughing at him until someone finally helped him out.

We had to go into a building filled with tear gas and remove our masks.

My fear of heights came to the forefront.

But I did ok with stamina.

Until we were taken to the “sand pits” for extreme Physical Training.

Anytime a platoon didn’t perform to expectations on the obstacle course or other activities they were taken to the “sand pits”.

There we endured burpees, mountain climbers and the dreaded rotation of:

“stand up, fall on your back, on your bellies, on your backs, roll like a bug”, and so on.

One day, while we were in the sand pits for some transgression, Private Coleman, from Texas, boldly said he didn’t do anything wrong and he wasn’t going to take punishment for the mistakes of others. The drill instructor smiled. He was so happy. He said, “OK Private Coleman, now your fellow recruits will pay for your defiance. Stand and rest and watch this. Here, have some water.”

The DI (drill instructor) then proceeded to put us through the worst workout we had ever had. Some recruits were dropping out from exhaustion or dehydration, some were vomiting. Everyone wanted to kill Private Coleman.

Because Coleman and Curran were so close in the alphabet, Pvt. Coleman and I were often next to each other in the same line. He lived in the hut with George and I.

When we returned to our hut, Coleman walked to the back of the building. I followed him, enraged. He was still mouthing off like a fool. I called his name and he turned around. I punched him square in the nose with all of my remaining power and anger. His blood splattered all over the back wall of the hut and on to freshly cleaned and tightly folded clothing that was ready for the dreaded “inspection” that was upcoming.

His Texas buddies rushed to his defense and George and the Chicago crew covered for me.

The Texans said I was a coward for punching him without warning. (The rule on the south side of Chicago was, if you think you are going to be in a fight, throw the first punch.)

In the meantime another group of angry recruits came to kick Coleman’s ass. We stopped them at the door and told them that it’s over. He’s “squared away”.

The DI came in later and saw the blood on all the white T shirts. “What happened here?” he said angrily.

The Texas crew told him that I attacked Coleman and caused the blood stains.

The DI went to look at Coleman’s face. His nose was flattened.

Then he walked up to me and put his face close in to mine.

“Good work Pvt. Curran, make sure this mess is cleaned up before inspection.”

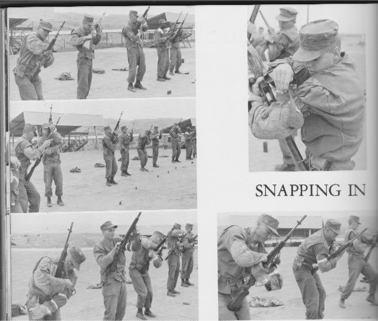

About midway through our training, we went to the rifle and pistol range for 2 weeks.

Learning to shoot a rifle was a tedious and painful task. The rifle strap had to be tied tight around your left arm, (snapping In), to enforce and learn the correct position. We held our unloaded rifles in position on a target for long periods of time until our arms went numb. The pain was excruciating but no one dared to complain.

We were forewarned that if we turned around and faced an instructor with our loaded rifle pointed in his direction, we would be shot without warning. There were stories of angry boot camp recruits turning their weapon on their DI with deadly results.

We fired many rounds without ear protection. At the end of each day everyone had severe ringing in the ears and difficulty hearing.

I did well shooting a 45 caliber pistol. A range instructor asked me where I was from and I told him Chicago. He said, “That figures”.

After the rifle range we returned to our normal routine of continuous physical training.

We were all exhausted and broken down.

Every day there were sit down classes. We quickly learned the art of sleeping for a few seconds while sitting up straight.

I have spent so much time standing in line in Catholic Schools and in the Marine Corps. The lines rarely led to anything good. To this day I am very edgy and impatient in lines.

No one was happy with anything. The food situation was really depressing.

“Maybe someday we will have time to chew our food.” “Maybe the food will be better at the next step of our training.” Maybe, maybe, maybe was the ongoing wishful thinking of stressed out young men.

“When I say ‘ready, sit’, you maggots better slam your asses on the bench quickly and at the same time. We will repeat it until you morons get it right.”

The allotted 70 days of boot camp went on past Christmas and New Year’s without any contact with the outside world other than letters from home. One day bled into the other. A little sleep, a little food, and a lot of work.

Towards the middle of January 1968 we were told that graduation day was coming soon and we would be tested on our physical abilities, combat readiness, plus knowledge of basic weapons and all things Marine Corps related.

The Combat Readiness drills and testing were tough but at least we were learning survival skills. Everyone was tired of the “chicken shit” marching drills and study of Marine Corps tradition. Let’s get on with it and go kill some commies, (for christ).

We started to feel some degree of confidence. We had all hit rock bottom. We had lost our individuality. They were starting to build us back up into their image of a fighter. We might actually pass our testing and move on to the next level of training.

The thought of going to Vietnam sounded foolishly inviting. Maybe we could get a cold beer and more sleep than was possible in boot camp.

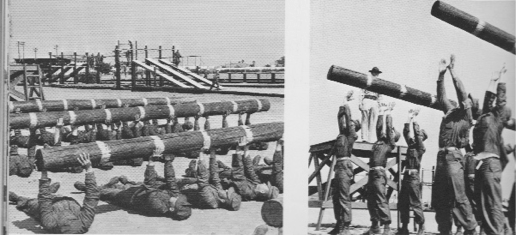

Teamwork

Or not

Things were getting very serious.

George and I passed our shooting tests with rifle and .45 caliber pistoI. We succeeded in combat readiness and the “academic” testing. In the Physical Fitness test I sucked at crunches and barely passed that portion with a minimum score. George aced it without taking a deep breath. He had the original 6 pack that was really a 12 pack. Later in his Marine Corps tour he went on to earn hundreds of dollars against unwitting marines, betting that he could do hundreds of sit-ups.

That’s me in the forefront.

Losing my religion.

Graduation! We were now considered Marines instead of slimy recruits.

It meant 3 things:

We were done with this brutal training.

We had to go to Camp Pendleton for Infantry and Specialty Training.

We were that much closer to going to Vietnam.

Best buddy, George Ruff.

George, front and to the viewers’s right

“One, Two, Three, Four

I love the Marine Corps”

That’s the story of George and Tom’s excellent adventure in Marine Corps Boot Camp.

I guess in the long run we came out ok.

After our graduation we were ordered to Camp Pendleton for “ITR”, (Infantry Training Regiment), for 4 weeks of Rifleman Combat Training. Then we would spend 4 weeks in “BITS”, (Basic Infantry Training School), where we would receive an MOS, (Military Occupational Specialty). At BITS we would be trained on a specific type of weaponry. (e.g. artillery, machine gun, anti tank weapons, or mortars)

Further Background:

I was reluctant to write about the caliber of men who were with us in boot camp.

They were from all over the country but heavily from the south. Many black men were there through the coercion of the courts to avoid jail time for various offenses.

I do not want to disrespect anyone but some of the recruits, white, black, and Hispanic had difficulty following even the simplest of instructions.

Our drill instructors were frustrated with the high number of somewhat illiterate or developmentally challenged young men.

On our first day of training, one DI asked for all those who had attended any college classes to step forward. Maybe 8 or 10 of us did so, (out of about 75 recruits). We were immediately assigned to clean toilets as part of our “extra duties”. This clearly demonstrated a contempt for educated people.

But on the other end of the scale the DIs were particularly brutal and demeaning to the recruits with apparent low aptitude. There was talk of lowered standards in order to get fresh meat into the military for service in Vietnam. A large percentage of young men at that time were in college and enjoying a deferment from the draft.

An old friend from Chicago recently sent me a web link that was related to this subject. A summary is below. I wonder how much time we spent in the “sand pits” because of these poor fellows.

Books and articles about the Vietnam War tend to focus on “the best and brightest,” whether to praise them for superior performance or to criticize them for failures in judgment and not measuring up to their promise. Author and Vietnam veteran Hamilton Gregory, however, examines servicemen at the opposite end of the ability and intelligence spectrum—the men inducted under the Pentagon’s “Project 100,000,” which began in October 1966.

The brainchild of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s defense secretary, Robert S. McNamara, and thus inevitably called “McNamara’s 100,000,” the project was a way to meet the manpower demands of an escalating war. Unwilling to fill the ranks through politically risky policies such as drafting college students or deploying large numbers of National Guard and Reserve personnel to Vietnam, the Johnson administration turned to the pool of men the president privately termed “second-class fellows.”

The project extended eligibility for enlistment and the draft to previously ineligible low-IQ men—those in the bottom tiers of the Armed Forces Qualification Test—and to some men who earlier would have been deemed medically unfit. The continuing program was planned to bring in 100,000 men each year.

Altogether, 354,000 substandard men were drafted–many sent directly into combat. In time, sergeants and officers, even General Westmoreland, called Project 100,000 a disaster. The low IQ soldiers were incompetent in combat, putting themselves and their comrades in danger. Inevitably, their death toll was appallingly high.

(Think Forrest Gump and his buddy,Bubba Blue)

http://medicinthegreentime.com/mcnamaras-folly-project-100000/